Fifty Years On,

Tracing the Magazine’s Role as a Medium

Jieon Shim, Editor in Chief

Special Feature

Cover of the first issue of Quarterly Art

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of Monthly Art. On the threshold of this milestone, the editorial team has launched a project that examines the magazine’s publications, charting the development of its heritage. Over the years, the magazine has undertaken several cataloging efforts, including the publication of a comprehensive index for the 30th anniversary and a compilation of major articles for the 300th issue. To mark the 50th anniversary, we are conducting an in-depth analysis of the magazine’s content drawing on these article lists. This report, prepared in commemoration of Issue No. 490, retraces 49 years of history through the magazine’s key articles and reassesses our role as a medium. Through this process, we reaffirm the trajectory of Monthly Art, which has consistently carried out long-term investigative reporting, compiled archival materials, and closely examined diverse issues with professional insight: a practice that sets it apart from from newspapers or books.

From Quarterly Art to Monthly Art

The history of Monthly Art begins with Gyeganmisul (literally “quarterly art,” hereafter Quarterly Art), launched in 1976 by the JoongAng Ilbo and the Samsung Foundation of Culture. The late 1970s marked a period when Korea’s economic growth paralleled the expansion of the institutional frameworks for art across both public and private sectors, giving rise to the nascent art market. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art was preparing to relocate from Deoksugung’s Seokjojeon Hall to its Gwacheon premises, and the Art Hall of the Korean Culture and Arts Foundation, which later became the ARKO Art Center (Arts Council Korea), opened in 1974. This was followed by the establishment of the Ho-Am Art Museum in 1982, funded by private capital. During this period, many local governments began actively discussing the establishment of founding municipal art museums to foster regional art and expand cultural access for citizens. These institutional developments laid the groundwork for the formation of a fully-fledged art market. From the early 1970s, galleries began opening in areas such as Myeong-dong and Insa-dong; in 1976, the Galleries Association of Korea was established to create a structured channel through which artworks could be presented to the public and collectors. The emergence of these institutions and the formation of the art market marked a shift in the art ecosystem, in which state-founded and state-led art systems—such as the National Art Exhibition and the Korean Fine Arts Association—were bolstered by private capital.

uarterly Art was the only art magazine published by a newspaper company, positioning itself as a comprehensive art and culture journal covering both modern and antique art. The quarterly cycle allowed for in-depth planning and a high level of professional expertise, laying the foundation of Korean art and establishing the magazine as a beacon of art journalism throughout the 1970s and 1980s.1 In January 1989, Quarterly Art changed its name to Monthly Art (also known as Wolganmisul in Korean). On December 14, 1988, The JoongAng Ilbo published an article titled “JoongAng Ilbo Launching Monthly Art” announcing that the new monthly journal would inherit the 13-year (47-issue) tradition of Quarterly Art and serve as a comprehensive medium scrutinizing contemporary art culture in the era of art popularization. Throughout the 1980s, the art-appreciating public expanded rapidly, and demand for domestic and international art information grew explosively in both quantity and quality, prompting the switch to a monthly format.

This transition meant more than a shift in publication frequency and marked a turning point in Korean art journalism. The new mission of the magazine was to bring art-world issues swiftly into public discourse through immediate on-site reporting and information sharing, to respond proactively to globalization by offering extensive coverage of international art news, and to expand its readership to include both professionals and general art enthusiasts. Under the declaration to “move beyond the narrow meaning of art and shed light broadly and deeply on all forms of art that unfold in our daily lives,” Monthly Art signaled the magazine’s role as a bona fide professional art medium, expanding both its archival scope and the breadth of discourse.

Historical Archive and Reconstruction: Filling the Gaps in Lost Art History

One of the most prominent early achievements of Monthly Art was its excavation and illumination of materials, filling the historical gaps in modern Korean art history that had been severed or distorted by liberation, war, and ideology. By documenting and accumulating them, the magazine provided primary source materials for art-historical research.

From Spring 1980 through Winter 1983 (Issue 28), Quarterly Art ran a special feature on modern art titled “Recovering Forgotten Modern Art,” which brought 45 previously unpublished works to light, bringing those long-buried modern pieces to serve as key resources for Korean art history. It highlighted unknown practices and forgotten works by modern masters such as Kim Junghyun, Ko Huidong, and Gu Bon-ung, fulfilling its purpose as a magazine that “uncovers and generates sources” for the study of modern art history.

The magazine was the first medium to address the issue of artists who had defected to North Korea. The Autumn 1985 issue’s feature “Living Testimonies: Artists of the Korean War Era,” was the first to record the names of North Korean-defected artists in Korean art history. This was a bold undertaking at a politically sensitive time, only three years prior to the official lifting of restrictions on North Korean artists. After the 1988 lifting of the ban, the magazine conducted in-depth reporting on the lives and works of North Korean-defected artists such as Jeong Jong-nyeo, Lee Quade, and Jeong Hyun-ung, thereby reconnecting the severed art histories of South and North Korea. Since the 1985 feature, Monthly Art has continued its investigative and discovery efforts regarding North Korean-defected artists. This sustained effort was driven by a mission-oriented determination: “to bridge the gaps in Korean art history, it was necessary to restore the art-historical significance of artists who had been obscured by the narrative of defection to the North.”

The “Excavation” and “Exploration” series in Monthly Art have played a crucial role in filling the gaps in modern and contemporary Korean art history. In the Summer 1981 issue, the magazine covered the New York studio of female painter Paik Nam-soon, rediscovering the artist after fifty years and sharing with the art world her firsthand accounts of life in New York along with her works. From October 1992 to March 1993, the magazine conducted an extensive survey of classical Chinese painting and calligraphy within Korea, and in 1993 it published exclusive rediscovery articles on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (who passed at 31) and the Korean-Uzbekistani artist Nikolay Semenovich Pak, thereby reinforcing its mission as a medium of documentation and an archival resource.

January 1989 issue of Monthly Art

Critical Public Sphere: Fierce Debates over Colonial Legacies and Postmodernism

Over the years, Monthly Art has stood at the center of major controversies and debates in the art world. It has not eluded sensitive issues or long-unresolved topics; it has confronted them boldly through ambitious editorial planning, bringing them into public discussion and broadening the discursive space.

In the Autumn 1979 issue of Quarterly Art, the article titled “A Ten-Year Assessment of Korean Heritage Painting” challenged the prevailing atmosphere in the art world, where government-led cultural policies were met primarily with silence or bland affirmation. The piece critically reevaluated the Korean Heritage Painting Exhibition (1967–1978), marking the first major critique of the state-led art documentation initiative and laying the foundation for art–historical research on the program in the late 1990s.

The Spring 1983 issue’s feature, “On Addressing the Japanese Colonial Legacy in Korean Art,” sparked the most intense debate in the art world since liberation. Progressive and reform-minded writers, including Kim Yoon-Soo, Lee Kyungsung, Lee Gu-yeol, and Choi Sunu, highlighted the colonial remnants the art world needed to confront and controversially identified 43 artists as pro-Japanese collaborators. In response, 36 art organizations issued a joint statement. Critics and various sectors, including the Korean Art Critics Association, expressed agreement with the need to purge colonial legacies and support for the magazine’s critical approach, fueling heated discussions throughout the art world.2 Through this article—recorded as “the largest post-liberation event to shake the art world”—Quarterly Art boldly ventured into the taboo territory of Japanese colonial remnants and played a pioneering role in publicly addressing art-historical facts that had previously been considered off-limits.3

When postmodernism gained prominence as a new intellectual current in the late 1980s, the magazine served as a formative platform that initiated debates and pushed the discourse in layered and multidimensional directions. As Hye Jin Mun notes, the Spring 1987 feature in Quarterly Art magazine, “Key Figures of Late Modernism,” was among the earliest Korean responses to developments in Western theory, which helped open critical discussion within the Korean art world. This approach signaled a shift from the previously unilateral mode of reception and instead sought to situate postmodernism critically within the Korean context, expanding the discourse on terms grounded in local conditions. At a time when the modernist and Minjung Art camps were formulating their positions and selectively appropriating postmodernism according to their respective logics, the magazine provided a balanced platform for both sides, creating a forum for rigorous debate within its pages. This demonstrated Monthly Art’s commitment to functioning as a public sphere and discursive arena—one that rejected ideological alignment and instead fostered sharp intellectual contestation. Furthermore, at a time when translated theoretical texts were scarce, the magazine played a crucial role in expanding the scope of art theory in Korea by publishing Korean translations of major international critics such as Fredric Jameson, Eva Cockcroft, and Hal Foster. These efforts helped deepen and diversify the discourse on postmodernism in the Korean art world.

In addition, Monthly Art has consistently monitored issues of artistic censorship arising both within and outside political and institutional spheres, using its pages as a platform to bring these matters into the public arena and to sustain its role

as documentation of history. The magazine has reported on the 2017 censorship incident surrounding the Young Artists Project in Daegu; conducted investigative coverage of the suspension of Statue of Peace at the 2019 Aichi Triennale; introduced Myanmar artists who resisted state censorship through their art in 2021; and covered the 2025 censorship controversy at the Seoul Museum of Art, documenting the unfolding events and the positions of those involved. These efforts have extended the isolated conversation on artistic censorship to a wider public sphere.

Examining the Art Market: Transparency Issues and Price Debates

Since the late 1970s, amid the rise of the “art boom,” Monthly Art has continuously tracked and analyzed the escalating prices of artworks, presenting in-depth articles well into the 1990s. The magazine’s first focused analysis of art prices appeared in the March 1989 issue, titled “Art Prices: Outrageous,” which sought to assess the factors behind the surge in market values. The October 1990 feature, “The Value and Cost of Artworks,” initiated a more inclusive discussion on the topic. At a time prior to established price benchmarks like auctions, the editorial team maintained a critical perspective on the steep price increases and the “name-your-price” phenomenon. They proposed an alternative framework for pricing based on artistic merit as evaluated by art critics. Through a survey of 20 art critics, the magazine categorized artists by genre and generation, quantifying the artistic value of works and analyzing their correlation with market prices. This approach provoked strong backlash in the art community. In response, the editorial team published a follow-up article under the heading “From the Editors,” explaining in detail the intention behind the feature, the relationship between artistic value and price, and the criteria and methodology used in selecting artists and critics, thereby asserting the critical legitimacy of their approach. While conceptually sound, the initiative of scoring artworks under the artists’ real names inevitably sparked intense debate.

Monthly Art’s concern over the art price phenomena continued in the October 1991 issue with the feature “Painting Prices: Then and Now,” following the changing contours in art prices from the 1960s through the 1990s. The magazine addressed the hoarding of artworks and the rapid escalation of prices, linking these phenomena to the introduction of the real-name financial system and policies curbing real estate speculation that emerged in the 1990s. Editorial board member Lee Kyuil noted that the absence of a formal pricing mechanism left artists to set their own prices, underscoring the need for both more influential galleries and an established auction system. Based on the magazine’s collected gallery price lists for different periods, Park Soo Keun’s paintings rose from 10,000 hwan (pre-won currency) in 1959 to 150 million won in 1991—a 15,000-fold increase—while works by Chang Ucchin were reportedly increasing by 10 million won per month. The article warned against the “folly of purchasing art as if speculating in securities,” urging buyers instead to “focus on the content of the work rather than the artist’s name.”

Subsequently, the May 1992 issue tracked fluctuations in the prices of popular artists’ works in the feature “Painting Prices in the First Half of ’92: How Much Have They Changed?” The January 1993 issue, “Special Feature on International Art: Rankings and Price Lists of 100 Leading Western Artists in 1992,” evaluated artists’ works and their pricing by referencing the key artist list published by German magazine Capital. Starting in June 1993, the magazine introduced a dedicated column, “Art Price Bulletin,” which examined efforts to standardize prices per canvas size unit (“ho” in Korean), the impact of the real-name financial system on the art market, and methods artists used to calculate their prices. After the establishment of Seoul Auction (then Seoul Gyeongmae, literally “Seoul auction”) in 1998, discussions of art prices shifted to market-wide assessments and analyses, a format Monthly Art continues to use for regular coverage of the Korean art market today.

Aspirations for Globalization and the Messenger of International Art

Beginning in the late 1980s, in response to the globalizing momentum of the art world, Monthly Art broadened its international coverage through sections such as “World News” and “World Report,” offering the Korean art world with an expanded global perspective. At a time when domestic access to international information was extremely limited, the magazine’s reporting stood as both a gateway to the latest developments in global art and a crucial site of learning. This shift eventually influenced its format: from the June 1999 issue to 2014, the spine and cover carried special-issue titles in English.

Special issues such as “World Artist 1997” (January 1997), “Retrospect & Prospect” (January 2009), “World Art Now” (January 2011), and “World Art News” (2011) offered detailed, regularly updated surveys of emerging spaces, events, award systems, and interviews with leading institutional figures across major hubs of global art such as New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo. Exhibitions and activities at Tate, MoMA, and the Centre Pompidou were considered essential points of reference, while major international events such as the Venice Biennale and the Whitney Biennial were consistent subjects of sustained coverage.

Monthly Art was also the first Korean art magazine to appoint overseas correspondents. These correspondents functioned not merely as channels of information, but as key mediators linking Korean art to the global art world. Among them were figures such as Seungduk Kim, Sook-Kyung Lee, Yeon Shim Chung, and Ahn Kyuchul, many of whom have since become leading curators,

theorists, and artists in the field. Drawing on the critical perspectives and international networks they developed abroad, the overseas correspondents endeavored to articulate the global positioning of Korean art while bringing major Western discourses and developments to Korean readers promptly and with critical insight.

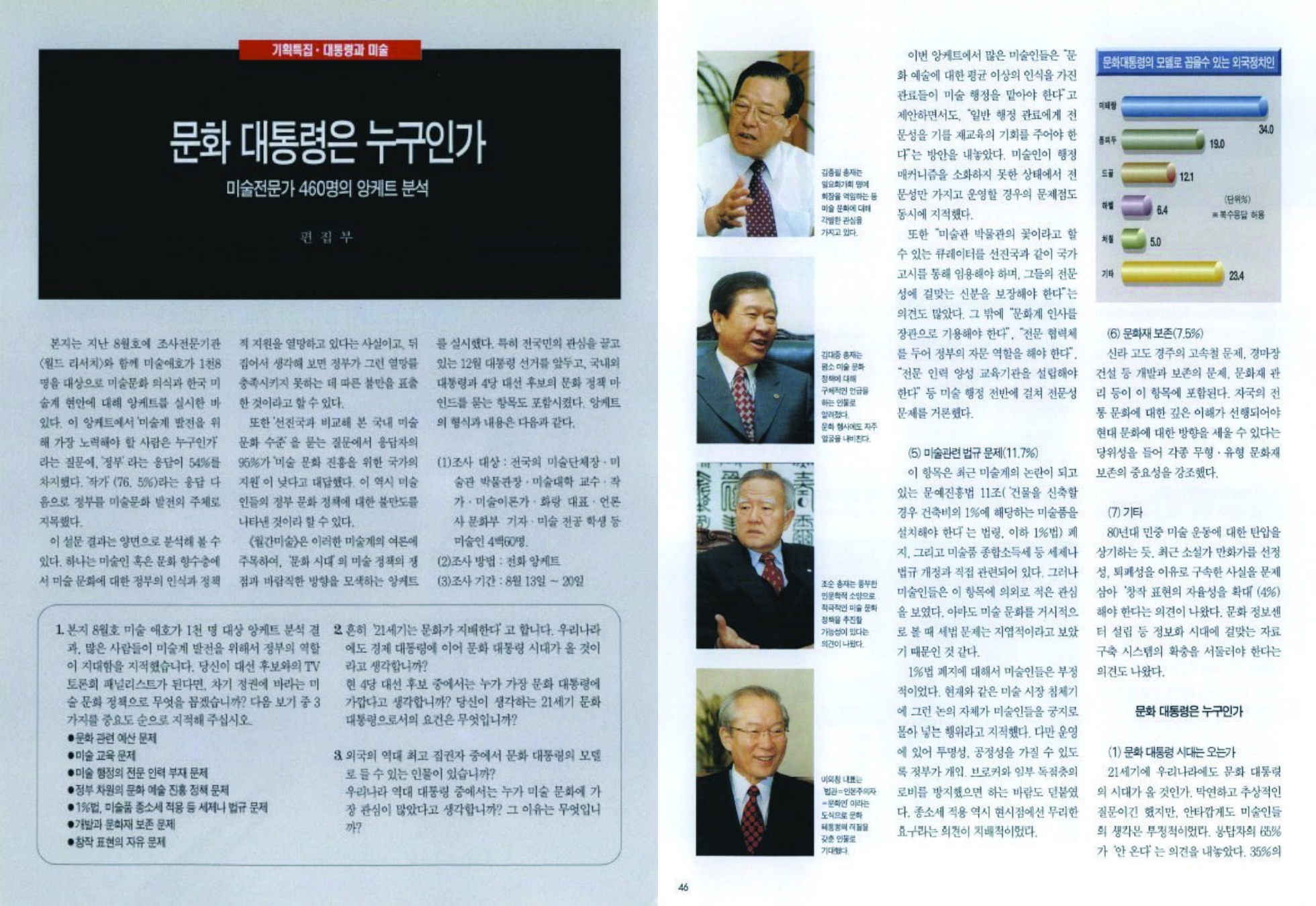

“The President and Art,” September 1997 issue of Monthly Art

Journalism that Expanded the Horizons of Art

In addition to numerous other significant initiatives, the following examples illustrate Monthly Art’s role as a specialized art publication.

When research into modern and contemporary Korean art was still in its early stages, the magazine pursued detailed studies of artists in collaboration with experts. For instance, the May 1994 special feature “This Is Su-Wha’s Art,” organized around the extensive 20th-anniversary retrospective of Kim Whanki, offered a critical and scholarly assessment of his oeuvre through collaborative expert research.4 The project examined Kim Whanki’s historical significance, artistic position, and the formal qualities of his work, aiming to elucidate the nature of Su-Wha: the artistic vision embodied in his works.

In the September 1997 issue anticipating the 15th presidential election, the magazine published a special feature, “The President and Art,” which gathered the opinions of artists on cultural policy and presented them to the campaigns of the four major presidential candidates, bringing these issues into public debate. Through interviews with candidates Lee Hoi-chang, Kim Dae-Jung, Kim Jong-pil, and Cho Soon, the magazine examined their party’s cultural policy proposals and their qualifications for cultural leadership. In these interviews, Kim Dae-Jung articulated the principle of “providing support without interference,” which later became a core tenet of his administration’s cultural policy (1998–2003). This initiative was significant as the first time in Korea that the art community publicly voiced its views on government cultural policy.

The February 2016 feature, “Hyunwook Hwang: Too Young for the Old Era,” brought attention to the once-forgotten gallery director Hyunwook Hwang (passed in 2001) and the gallery he founded, Inkong Gallery. Though it might be mistaken for a commemorative tribute, the feature was a journalistic effort to fill gaps in art history. Hwang played a pivotal role in promoting the value of Dansaekhwa artists and introduced international minimal art figures such as Donald Judd and Richard Long to Korea, thereby expanding the horizons of contemporary Korean art. By reevaluating his visionary projects and activities, the article highlighted the contributions of non-institutional figures who had been marginalized by mainstream discourse or overshadowed by commercial success, committed to the essential role of specialized art media in uncovering and reasserting artistic value.

Monthly Art facilitated connections between the globally renowned artist Nam June Paik and the Korean art world. The magazine’s engagement with Paik began in 1981, when its New York correspondent, Kim Jae-hyuk, tracked down the internationally renowned artist and visited his Soho studio. The resulting feature, “Nam June Paik – Cultural Terrorism,” introduced Paik’s life and artistic activities to Korea for the first time in decades. Over the years, Paik appeared in the magazine multiple times, playing a guiding role in the internationalization of Korean art. Following his passing in January 2006, Monthly Art published the commemorative special feature, “Bye Bye Nam June Paik,” which provided a comprehensive overview of the artist’s life, oeuvre, and statements, accompanied by illustrations of his works. In addition to expert analyses, the feature included interviews and memorial tributes from art and cultural figures from Korea and abroad closely associated with Paik, such as Bill Viola and Christo and Jeanne-Claude, as well as Yoko Ono, Lim Young-bang, Lee Youngwoo, Youn Myeung-Ro, Ahn So-yeon, Kang Taehi, Ryu Byoung Hak, Kim Yun‑sun, Lim Young kyun, Jin Youngsun, and Cheon Ho‑seon, sharing personal recollections of the artist. Furthermore, coverage of Paik’s funeral in New York by the magazine’s correspondent at the time, Yeon Shim Chung, vividly conveyed to Korean readers how the global art community bade farewell to one of the era’s most visionary figures, inscribing his legacy in Korean art history.

Within the pages of specialized art publications, critics and art magazines operate as co-producers of discourse, with the editorial space serving both as a springboard for emerging critics and as an official platform for their voices. In this context, Monthly Art has consistently featured special issues that analyze and discuss the realities and challenges of contemporary art criticism in collaboration with critics. Notable examples include the April 1997 issue, “Critic & Criticism,” the February 2003 feature, “Korean Art Criticism Now,” the March 2006 special roundtable, “What is Present in Korean Art Criticism,” and the March 2012 issue, “Hello, Critics!” These features trace the ongoing examination of the crises, fading influence, and the contemporary landscape of art criticism in Korea.

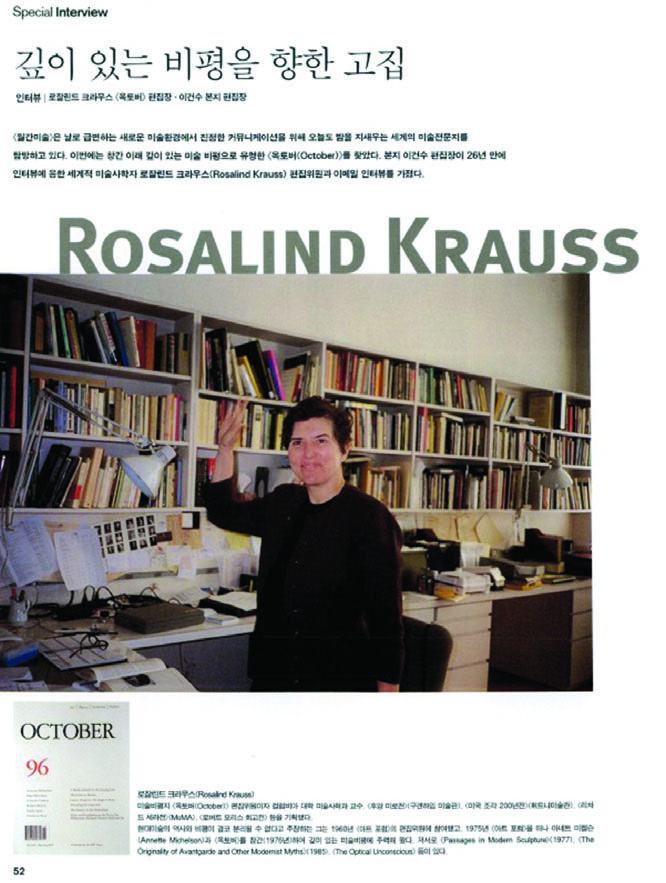

Between 2001 and 2002, Monthly Art carried out a series of interviews with editors-in-chief of leading international art magazines, a project that fundamentally explored how publications shape art discourse amid the rapid globalization and digitalization of the early 21st-century art world. The interviewees—Frieze, Artbyte,

and October—each represented distinct axes of influence: popularity, technology, and criticism, respectively, demonstrating the evolving social role of each publication and its responsiveness to contemporary sensibility. This series of interviews posed fundamental questions about the role of contemporary art journalism, while offering a reflection on the rapidly changing media landscape. Through examining each magazine’s unique readership and editorial philosophy, the series provided profound insights for the trajectory that both contemporary art and art journalism should chart.

The second round of international editors-in-chief interviews was conducted in 2010 to mark Monthly Art’s 300th issue. The questionnaires sent to the editors-in-chief from Art in America, Frieze, Flash Art, and Bijutsu Techo addressed the state of art journalism in their respective countries, the fate of print magazines, their views on contemporary Korean art, and the trajectory of their publications, reflecting on the position, role, and future of art journalism. To complement the early 2000s focus on the Americas and Europe, the series also included China’s Art Criticism and Japan’s Bijutsu Techo, expanding the scope to Asian art journalism. This global dialogue demonstrates how the magazine extends its coverage from the domestic art scene to engage with international discourse.

“Special Interview: A Stubborn Pursuit of Deep Criticism — Rosalind Krauss, Editor of October,” July 2001 issue of Monthly Art

Changes and Challenges: Renewal, Thematic Issues, and English Editions

Over its 49-year history, Monthly Art has undergone several renewals, updating both its appearance and content. Most recently, in April 2024, the magazine unveiled a fully redesigned issue featuring a new editorial direction and layout. This renewal involved changes in format and title, along with multiple innovative adjustments in design and editorial approach—a manifestation of the editorial team’s strong commitment to transformation. While the magazine carries a deep tradition and history built over decades, there were many aspects that required adaptation. As a renewal goes far beyond a superficial makeover, the process also entailed numerous changes to the underlying principles, structures, and commitments that drive the making of each issue. Monthly Art stands as a testament to the editorial team’s thoughtful engagement with the challenges and crises facing print media today.

After reorganizing its publishing format, the magazine introduced “thematic issues,” with each issue focused entirely on a single topic. The first of these thematic issues, titled “Museum for All?” addressed questions of inclusivity in museums. It was highly praised by stakeholders for its timely and thoroughly structured content, and has been frequently used as a practical reference by relevant institutions, much like a white paper.

With the accelerated globalization of the Korean art scene following the co-hosting of KIAF and Frieze in 2022, Monthly Art began producing special English-language issues for visiting international experts and art enthusiasts. Though primarily published in Korean, the magazine produces an annual English issue each September, distributed free, to introduce the authentic face of contemporary Korean art to a global audience. The 2024 issue focused on Korea’s major biennales, the Gwangju and Busan Biennales, linking the content with the contexts of hosting cities. This year, responding to questions from international audiences such as “Where are contemporary Korean artists emerging today, and where can we encounter them?” Monthly Art published “Boiling Point: Emerging Artists and Spaces in Korea.” The issue introduces eight initiative spaces in Seoul that have been actively operating since 2020 and eight artists highlighted by each space director. Whereas most English-language content focuses on major institutions and well-known figures, Monthly Art creates and distributes its English edition around readers’ genuine interests, offering an introduction to Korean art shaped by that perspective.

So far, we have glanced through the major special features and editorial direction of Monthly Art over its 49-year history. While every article published across the 489 issues holds unique significance from the editorial perspective, space constraints have necessitated selective coverage. More detailed examples organized by category are presented in the following analyses by the editorial team, and the relationship between art magazines and art criticism is treated at length in an essay by critic Junghyun Kim.

*Korean-English Translation of this text is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service

1 In-kee Ahn, “A study on the Formation and Function of Magazine Journalism in Korea” The Journal of Art Theory & Practice 0, no.2 (2004) : 121-146.

2 Detailed coverage of this debate can be found in the Kyunghyang Shinmun, April 25, 1983, p. 7, and the Dong-A Ilbo, April 30, 1983, p. 10.

3 Lee Kyuil, “The Inside Story of Pro-Japanese Painter Cha Dong,” Monthly Art, August 1990, p. 146; Woo Jinyoung, “An Analysis on the Feature Articles of Art Magazine GYEGANMISUL in the 1980s,” Journal of Korean Modern & Contemporary Art History no.45(2023) : 213-236.

4 Translator’s note: “Su-Wha (樹話)” is Kim Whanki’s pen name, combining the Chinese characters for “tree” (Su, 樹) and “narrative” or “talk” (Wha, 話), symbolizing a dialogue with trees and the interconnected natural elements within his work.

*Translation by Jin Young Koh

© (주)월간미술, 무단전재 및 재배포 금지