Climate Forecast:

Shifts in Art Magazines and Criticisms

Junghyun Kim (Art Critic)

Special Feature

“Survey and Analysis of 74 Korean Art Critics and Theorists,”

April 1997 issue of Monthly Art

Positioning

Opening this topic, I would like to first situate my position. As an art critic, I began contributing art-critical writing in 2011. My first piece was a short prefatory essay for a show titled Dongbang Yogoi (literally, “Monsters of the East”), which marked my first foray into “on-site criticism.” The exhibition—a group show for emerging artists curated by Art in Culture—paired me with one of the participating artists. Shortly thereafter, through an introduction from an acquaintance, I began writing on a relatively regular basis as a contributing critic for the quarterly Contemporary Art Journal published by Sang-yong Shim. It was only in late 2015, after receiving the SeMA–Hana Art Criticism Award that December, that I began identifying myself officially as a “critic” in my professional affiliation rather than adhering to my academic training as an “art historian.” From the following year onward, that recognition led me to contribute to several major monthly art magazines—including Artworld, Monthly Art, Public Art, and Art in Culture. Once formally acknowledged as a critic, I received a wide array of commissions from institutions and media outlets, far more than in my days as a fixed contributor to a quarterly journal. Unlike before, when I had greater latitude in choosing my subjects, many of my later topics were determined by external invitations.

At the award ceremony for the SeMA–Hana Art Criticism Award held by the Seoul Museum of Art, the 2015 Korean Contemporary Art Criticism Forum was convened, during which critic Hye Jin Mun publicly raised the issue of working conditions for writers, specifically calling out nonpayment of fees by specialized art magazines. In the first issue of Monthly Art in 2016, an article appeared under the title mirroring her forum presentation: “The Reason Why Contemporary Korean Art Criticism has been Absent.” Looking back on the situation roughly a decade ago, when promised honoraria were often delayed or simply never paid, the current labor conditions may seem relatively stable. The rate increases for magazine payments stays minimal—not even keeping pace with inflation—, yet awareness around carrying out contracts has at least improved. In that same essay, Mun emphasizes the significance of art magazines for critics: “The pages of specialized art periodicals are both a steppingstone for critics to gain exposure and an official platform for their voices. Since the magazine’s editorial mandate is set a part from the commissioning body and the subject of criticism, it provides the only space where one can speak transparently about exhibitions or pressing issues without direct conflicts of interest. Moreover, contributors are selected by the editorial team precisely because they are the most relevant writers for that subject. That is why, for critics, the pages of a magazine serve as the most recognized public institution—a space in which the very act of writing affirms one’s professional standing.”

Having established myself as an emerging critic and spent over a decade navigating various editorial platforms within Korean art institutions, I have come to deeply resonate with Mun’s account of art magazines. Ethical challenges often surface when specialized publications operate outside rigorous editorial standards, yet art magazines remain a rare and precious medium. Compared to artist research or exhibition catalogues, which demand close collaboration with the subject of study, magazines uniquely guarantee a writer’s independent and autonomous thinking. From that perspective, I conceived this piece quite deliberately, in contrast to most institutional art writing that focuses on artist theory or curatorial themes. Observing how Monthly Art contributors make use of the pages provided through the KAMS (Korea Arts Management Service) Korean Art Criticism Support program offers a reciprocal lens into both the editors’ expectations of critics and the critics’ own vision for art magazines. Having sketched out one’s hopes through his experience, now it suffices to explore the approaches of other critics.

The Climate of Criticism

Looking through the archive of criticism and journalism in Monthly Art, the climate of art criticism that extends into the mid-2020s appears to have taken shape largely in the late 1990s to the early 2000s. To sketch the historical shift of Korean art criticism and media landscape: in the earlier era, artists often combined practice with writing, while full-time critics such as Lee Kyungsung and Lee Yil emerged in the 1960s–70s; in the following decades into the 1980s, the pages of art journalism—magazines like Monthly Art and newspapers—expanded; and from the 1990s onward, the traditional gateway of debuting via daily newspaper’s Sinchunmunye (meaning “Annual Spring Literary Contest”) was broadened to include art-specialized magazine competitions (such as the Wolagnmisool Art Awards, 1996–2012, 2022-), as well as recommendations by critics and experts. Entering the 2000s, both art critics and art magazines grew

in number, in step with the rapid expansion of the art market and institutional frameworks. At the same time, the art coverage in daily newspapers—one of the two pillars of art journalism—began to shrink; notably, the Sinchunmunye art category of the Dong-A Ilbo was discontinued in 2002. These shifts likely heightened expectations for art-specialized publications such as Monthly Art to assume on a more central role.

In the 2006 roundtable organized for Monthly Art’s 30th-anniversary issue, titled “Korean Art: An Uncomfortable Cohabitation with the Press,” art critic Lee Sun Young—then an editorial board member of the webzine Art&Discourse—remarked that “daily newspapers are reluctant to allocate space to specialized writers with a critical perspective.” In response, Roh Hyungsuk, Arts Reporter on the Culture Desk of the Hankyoreh, argued: “Newspapers do, in various ways, reflect what they recognize as trends. (…) But there needs to be a structure that allows genres or areas of interest to branch into finer layers according to differing tastes and concerns. (…) The art field …suffers from a severe lack of such genre-based infrastructure. In the end, commercial shifts are presented as the only viable alternative—lacking in long-term vision or reflection. The overarching disappearance of professional contributors from newspapers, and the marginalization of reviews and substantive criticism, can be traced to these conditions.”

The voices of numerous critics have carried the demand for both engagement and professional rigor in Korean art criticism around the turn of the 2000s. “There is still a lack thorough research into establishing a coherent art history or a proper methodology for criticism.” (Kang Taehi, 1997) “Corresponding to our increasingly segmented era, criticism must also be specialized and differentiated (…) yet even then, the specialization of criticism should resist being segregated by the disciplinary lines—such as painting or sculpture, Western-style or Korean.” (Oh Kwang Su, 2003). “Though most critical writing appears in art magazines, it tends to remain in the form of short reviews or generalized commentaries. Overcoming the accustomed brevity in art criticism will require a radical expansion of printed space—magazines, seminars—so that critics can publish academic-level articles (Choi Byungsik, Hun Yee Jung, Sun Hak Kang, Kim Sangcheol, 1997).” “Criticism must be grounded in hak (學, the science of scholarship). Defining field criticism or academic criticism is only a matter of terminology.” (Kang Sumi, 2006)

The need for probing research and its suitable platforms seemed to remained somewhat out of sync. Ahn In Kee, a critic and former editor for Monthly Art, directly criticized what he calls the “catalogue journalism” of art magazines in his 2006 essay “Art Magazine Journalism: Then and Now.” “Over the course of the 1990s, magazines increasingly geared toward monthly issues, full-color pages, and large-format layouts—shifting from text-focused to visually-oriented formats. (…) Magazines slowly transformed their position as a platform for enlightenment and education into that for differing information and promotional functions.” Ahn notably points out that magazines began focusing more on artists than on their works: “The artist must become the new spectacle and myth that magazines ought to construct, and the magazine guarantees the artist stardom and reputation.” He goes further: “Forecasting tomorrow’s ‘Van Gogh’ became one of a monthly magazine’s chief missions.” At once, as art magazines shifted their focus to global art scenes and concentrated on artist profiles and exhibition information, “the share of scholarship, theoretical discourse, investigative reporting, and critical commentary began to decline, gradually evolving into ‘catalogue journalism.’”

In the pages of 21st‑century art magazines—shaped by the discourse of exhibitions and the increasing internationalization of the art world—art criticism largely fell short of the expectations voiced in various surveys and roundtables. Yet this frustration was not due to the magazines’ “betrayal.” Shifts in the times and the media environment also undermined the centripetal influence and reach of art criticism. As the audience for criticism became increasingly limited, independent initiatives emerged, with critics producing their own mooks or quarterly journals as alternatives to mainstream art journalism. “We’ve been grumbling til now, and if there’s no scene, we make one ourselves.” Lee Daebum ran the small-scale publishing collective roundabout and published the mook debut. Sang-yong Shim became the editor-in-chief of the advertisement‑free quarterly, Contemporary Art Journal.

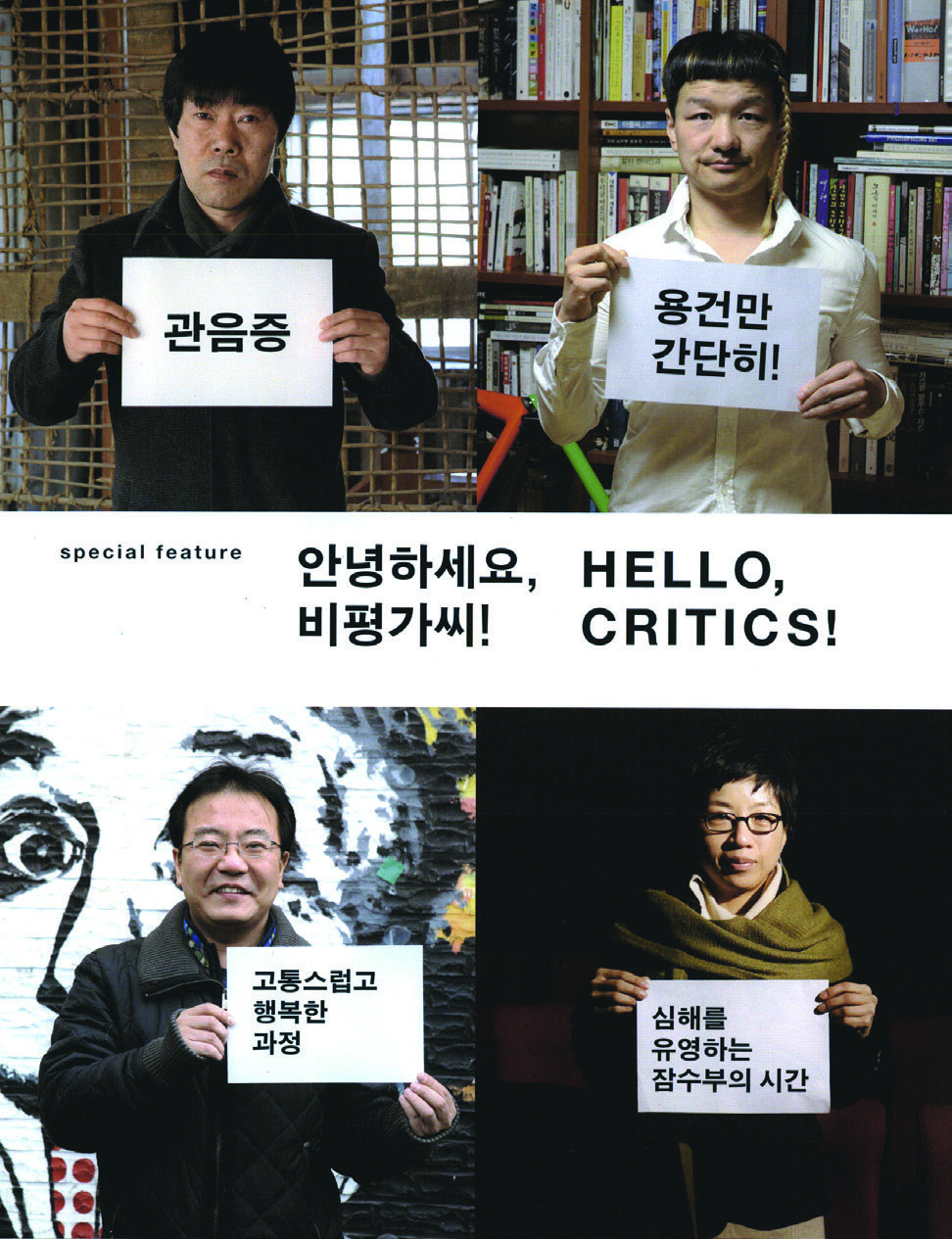

“HELLO, CRITICS!” March 2012 issue of Monthly Art

In 2012, Monthly Art launched the special feature “Hello, Critics!” which revealed the “variegated personas” of eight mid-career critics and created a site for “intimate confessions.” This distinctive feature included portrait spreads and inquired not only into each critic’s perspectives but also their personality and tastes. Highlighting critics as distinctive individuals beyond their writing appears to continue the trajectory set by the group exhibition The Scene of Criticism (2009) held at Ilmin Museum of Art and its related coverage. The fading cohesive space of art criticism in magazines is then occupied by the compelling individuality of the critics themselves.

Beyond the scope of this discussion—centered on the relationship between art magazines and art criticism—critical media continue to experience the quiet ebbs and flows typical of their history. Is criticism subject to the same fate? Kang Sumi, an art critic who for a time oversaw meta-criticism at Monthly Art, pointed to the pitfalls of the “crisis of criticism” discourse: “Riding on the worn-out narrative of criticism’s crisis, aimless chatter, false judgments, and superficial descriptions—licking their subjects’ surface—cloak themselves in the garments of meaning and present themselves as criticism.”

For Kang, who places strong trust in the reasoning power of criticism, “meaning unravels as the manifestation of the whole; thus, even if mass media appropriates fragments or the market repurposes them here and there, criticism will not be easily exhausted or undermined.” In other words, the troubles of critical media—including art magazines—do not automatically translate into a crisis for art criticism itself. Naturally, critics’ sense of crisis largely stems from the extent of the production and reception of criticism. For example: “Do art magazines seek art criticism?”

The significance of art magazines in sustaining art criticism was carried forward by an unexpected development. In 2019, the Korea Arts Management Service launched the “Visual Arts Critics–Media Matching” program aimed at professionalizing critics and making fees more realistic; it enabled a few critics to write one or two more pieces a year—texts like those the Monthly Art editorial team had hoped for in 1997. These were “texts of more than forty manuscript pages (…) capable of unfolding a critical perspective at length.” The initiative, which had raised concerns—of “not paying close attention to the fair distribution of opportunities for emerging critics” and of “ultimately remaining an ad hoc support measure”—has gradually evolved, and as of now (2025), continues in a form that entails and upholds the competence and ethics of participating media. It would be relevant to bear in mind that: “there are many areas that art critics ought to [critically] look into,” yet “the current landscape of criticism may be oriented toward texts serving as artists’ archives.”

In this article, the climate of art criticism is discussed within the relationship between art magazines and criticism, which introduce the concept of a “forecast” in the title. This idea was appropriated from another special feature in Monthly Art. In a piece on art journalism, the editor-in-chief of the French art magazine Beaux-Arts describes their publication to readers as “something like an aesthetic ‘weather forecast,’” and explains that “this is how aesthetic concepts spread.” Reconsidering this metaphor—originally meant to highlight the value of accessible, everyday information—we might apply it to the present and future relationship between art magazines and criticism. Perhaps, by analyzing art magazine archives and critics’ experiences, we might arrive at some plausible forecasts. Weather is capricious, yet that is acceptable—there are only a few days with unbroken sunshine. If art magazines genuinely desire art criticism, a climate crisis may not ensue.

*Korean-English Translation of this text is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service

1“2015 SeMA–Hana Art Criticism Award: 2015 Korean Contemporary Art Criticism Forum,” Seoul Museum of Art, 2015, pp.198-213; Hye Jin Mun, “The Reason Why Contemporary Korean Art Criticism has been Absent,” Monthly Art, January 2016. p.48.

2 Hye Jin Mun, “The Reason Why Contemporary Korean Art Criticism has been Absent,” Monthly Art, January 2016, p.48

3 See “Survey Analysis of 74 Art Critics and Theorists in Korea,” Monthly Art, April 1997, pp.48–66.

4 Choi Geum Soo, Lee Sun Young, Roh Hyung Suk, “Korean Art: An Uncomfortable Cohabitation with the Press,” Monthly Art, April 2006, p.179

5 Ahn In Kee, “What is Present in Korean Art Criticism,” Monthly Art, April 2006, p.176.

6 “Hello, Critics!,” Monthly Art, March 2012, p.101

7 “Hello, Critics!,” Monthly Art, March 2012, p.81, listed in the order of pictorials and individual articles Kho Chunghwan, Ban E Jung, Lee Daebum, Kang Sumi, Sang‑yong Shim, Geun‑jun Lim, Park Young-taek, Lee Sun Young

8 Exhibition introductions of the participating critics, Kim Hakryang, “The Scene of Criticism” (Review), Monthly Art, May 2009, pp.138-145.

9 For a discussion of changes in the context of art criticism beyond art magazines, see the following, Hye Jin Mun, “The 21st Century Witnessed by Criticism: Retrospecting 21st century from 21st Century (Thematic Feature),” Monthly Art, January 2020, pp.97-99.

10 Kang Sumi, “Special Feature: Why Should We Fear the Crisis of Criticism? Nine Critics Speak on the Korean Art Scene, Monthly Art, December 2013, p.89.

11 “Survey Analysis of 74 Art Critics and Theorists in Korea,” Monthly Art, April 1997, p.52.

12 The former, by Moon Junghyun, “The Musical Chairs of Art Criticism,” Monthly Art, May 2019, p. 58; the latter, by Hye Jin Mun, “The 21st Century Witnessed by Criticism: Retrospecting 21st century from 21st Century (Thematic Feature),” Monthly Art, January 2020, p.99.

13 Lev AAN, “The Age of Non-Criticism: Early Arrival, Void, Clearing in the Woods,” Monthly Art, December 2024, p.83.

14 Fabrice Bousteau, “The Failure of Many Magazines Comes from Boredom,” Monthly Art, January 2010, p.104.

*Translation by Jin Young Koh

© (주)월간미술, 무단전재 및 재배포 금지