GALA PORRAS-KIM

Multilayered Perspectives: Gala Porras-Kim

ARTIST REVIEW

Gala Porras-Kim is a Colombian-Korean artist. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Art and Latin American Studies from UCLA, a Master’s degree in Art from CalArts, and a Master’s degree in Latin American Studies from UCLA. Some of her notable solo exhibitions include Entre lapsos de historias (Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporaneo [MUAC], Mexico, 2023), Gala Porras-Kim: The weight of a patina of time (Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2023), Precipitation for an Arid Landscape (Amant/Kadist, 2021), and Open House: Gala Porras-Kim (Museum of Contemporary Art [MOCA], Los Angeles, 2019). She has also participated in significant group exhibitions, including the 34th São Paulo Biennial (2021), the 13th Gwangju Biennale (2021), the Whitney Biennial (2019), as well as exhibitions at venues such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA, 2017), and the Hammer Museum (2016).

Multilayered Perspectives: Gala Porras-Kim

Suyeong Lim | Art Historian and Independent Curator

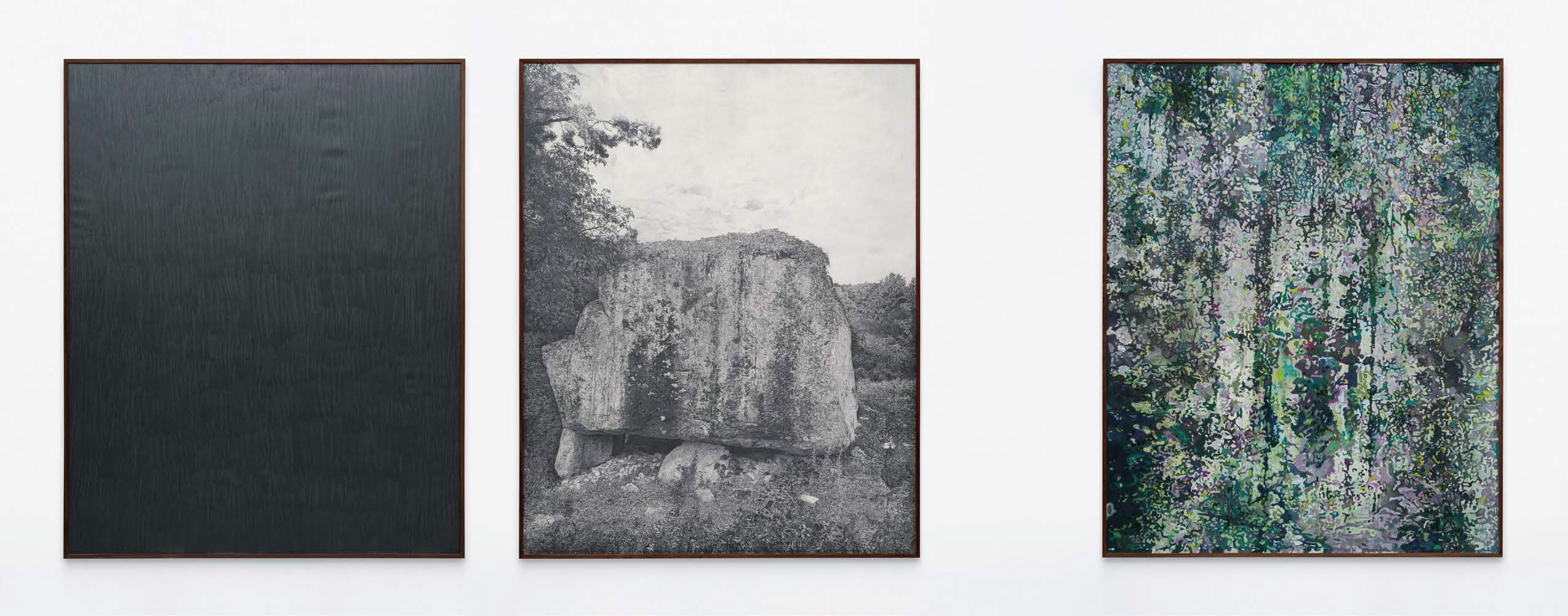

Gala Porras-Kim’s The weight of a patina of time (2023), consists of three large-scale drawings that depict the UNESCO World Heritage Site Gochang Dolmen from different perspectives. One drawing, filled with graphite, represents the darkness as seen from the perspective of those buried beneath the dolmen. Another drawing, sketched with a pencil, shows the current state of the dolmen as a protected cultural heritage site. The third drawing, done in colored pencil, illustrate the moss that has grown on the dolmen over time. This new work of art by the Korean-Colombian artist was showcased at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Korea Artist Prize Exhibition 2023. It’s intriguing to note that the title of this new piece is the same as her solo exhibition at the Fowler Museum in UCLA in the same year.[1] The exhibition, which took place from July 9 to October 29, 2023, featured Porras-Kim’s works from the previous seven years. In her art, the artist explores the impact of time on ancient artifacts and heritage sites and how they are conserved, categorized, exhibited, and described within modern systems such as cultural institutions and heritage structures.

[1] This exhibition, held from July 9 to October 29, 2023, showcased the works Porras-Kim had presented over the previous seven years.

Eternal Life

For Porras-Kim, objects are imbued with life, each possessing its own unique essence. The artist specifically examines objects that were created with the belief that their purpose and significance would endure indefinitely. This is due to the fact that ancient artifacts, originally crafted with reverence for life and death, lose their original function once they are unearthed from their long burial, and begin a new existence as museum pieces. These collections may undergo challenging times, such as extensive restoration, removal from museums, or loss of their status as artifacts. By tracking the journeys of these objects as they are placed and displaced based on contemporary needs and desires, often disregarding the intentions of ancient people, the artist questions actions and policies that have long been accepted without question under the pretext of preserving culture and history.

Exploring the (in)visible or (im)material information of already lost or deteriorated artifacts is like piecing together fragments into a coherent form. This process requires as much imagination as it does sharp analysis. Similarly, the artist does not view the institution of the museum as a subject of criticism or denial, but incorporates it as part of her creative process, treating it as a collaborator in an endeavor of shared exploration and imagination. A prime example is Precipitation for an arid landscape, which has been exhibited in various ways at several art and archeological museums. Harvard University’s Peabody Museum houses over 30,000 artifacts and remains from a natural cave, or cenote, which ancient Mayans considered as a sacred place where the rain god Chaac resided. These objects have been preserved and exhibited in a dry environment, thereby removed from the god of rain. In order to restore their ritual function, the artist collected dust from the collection and mixed it with copal tree resin, creating a new object. Institutions exhibiting this object must install it in a way that allows the dust-containing mass to make contact with rainwater, so that the artifacts can communicate again with the rain god. While the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea simulated rain using a humidifying effect, other museums have adopted methods such as letting curators spray water periodically or creating openings in the building’s ceiling to allow actual rain to fall, thereby creating “precipitation” in the “arid landscape.

Drawing as a Methodology

Porras-Kim’s preferred artistic medium is drawing, utilizing pencil, graphite, and colored pencil. She deliberately distinguishes her flat works created with easily accessible and usable materials as “drawings,” separate from traditional “oil paintings,”. Drawing is multidisciplinary and used in fields such as architecture, medicine, botany, and archaeology. It encompasses sketches and studies, embracing an unfinished state. This detailed depiction process, primarily based on actual artifacts or photographs, slows down the passage of time

and provides an opportunity to learn about the drawing’s subject, says Porras-Kim.[1] The meticulous act of capturing often-overlooked minute details of artifacts seems to “slow time,” serves to counters unique artist’s identity and the value of immediacy that hyper-capitalist society cherishes.[2] Completed in this manner, Porras-Kim’s drawings are divided into black-and-white sketches reminiscent of archaeological illustrations and colored versions that arrange various objects on a single plane.

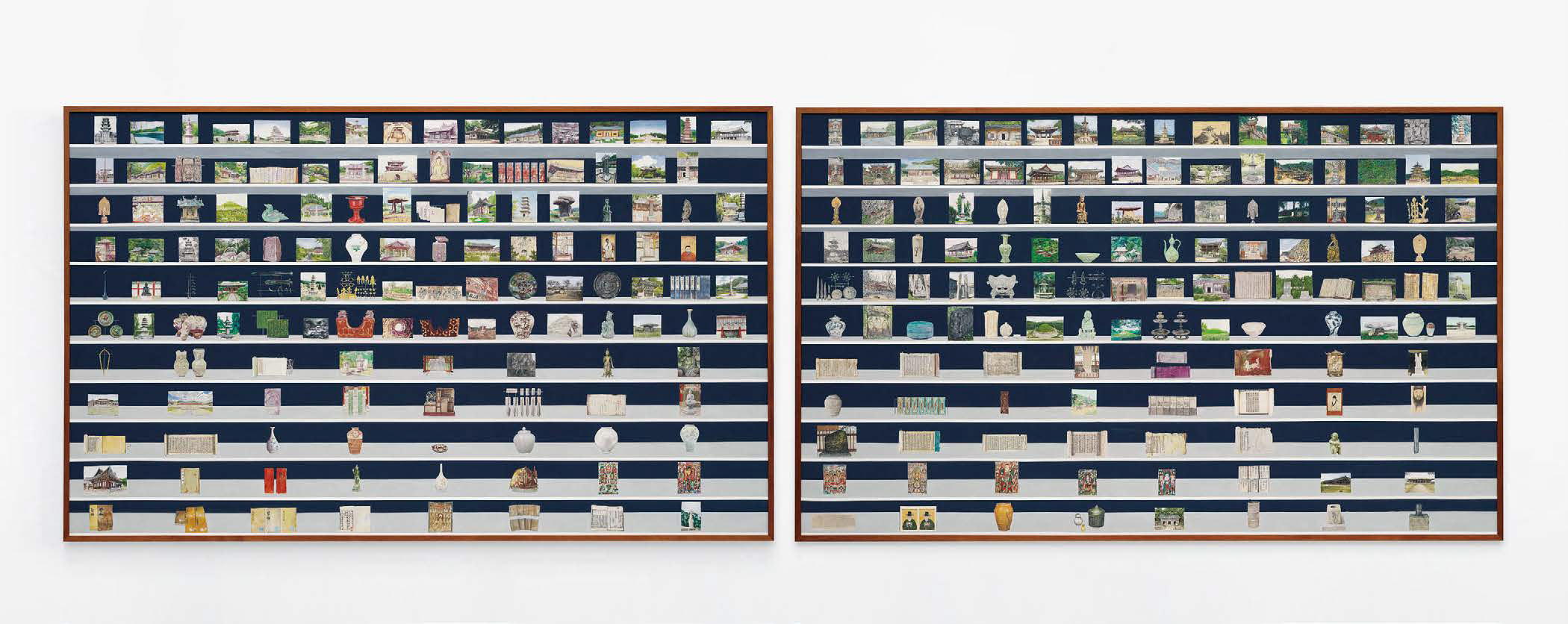

The artist views drawing as a way to learn, express, and organize thoughts while visualizing structural questions. In her 530 National Treasures (2023), presented at her National Treasure exhibition at the Leeum Museum of Art, the piece brings together cultural heritage items designated as national treasures by both South Korea and North Korea. This serves as a reminder that different national entities have managed cultural heritage according to their own logic and needs throughout history. The artist contemplated her drawing by depicting shelves, allowing the artifacts to appear as if they are floating within the frame until the last moment. However, the fact that objects placed arbitrarily on shelves can be taken out and rearranged at any time means that her work always holds the potential for change.

[1] Ricky Amadour, “An interview with “ Porras-Kim,” Riot Material, 2022. 1. 5.

[2] Anna Kornbluh, “Against Anti-theory,” e-flux, 2024. 2. 9.

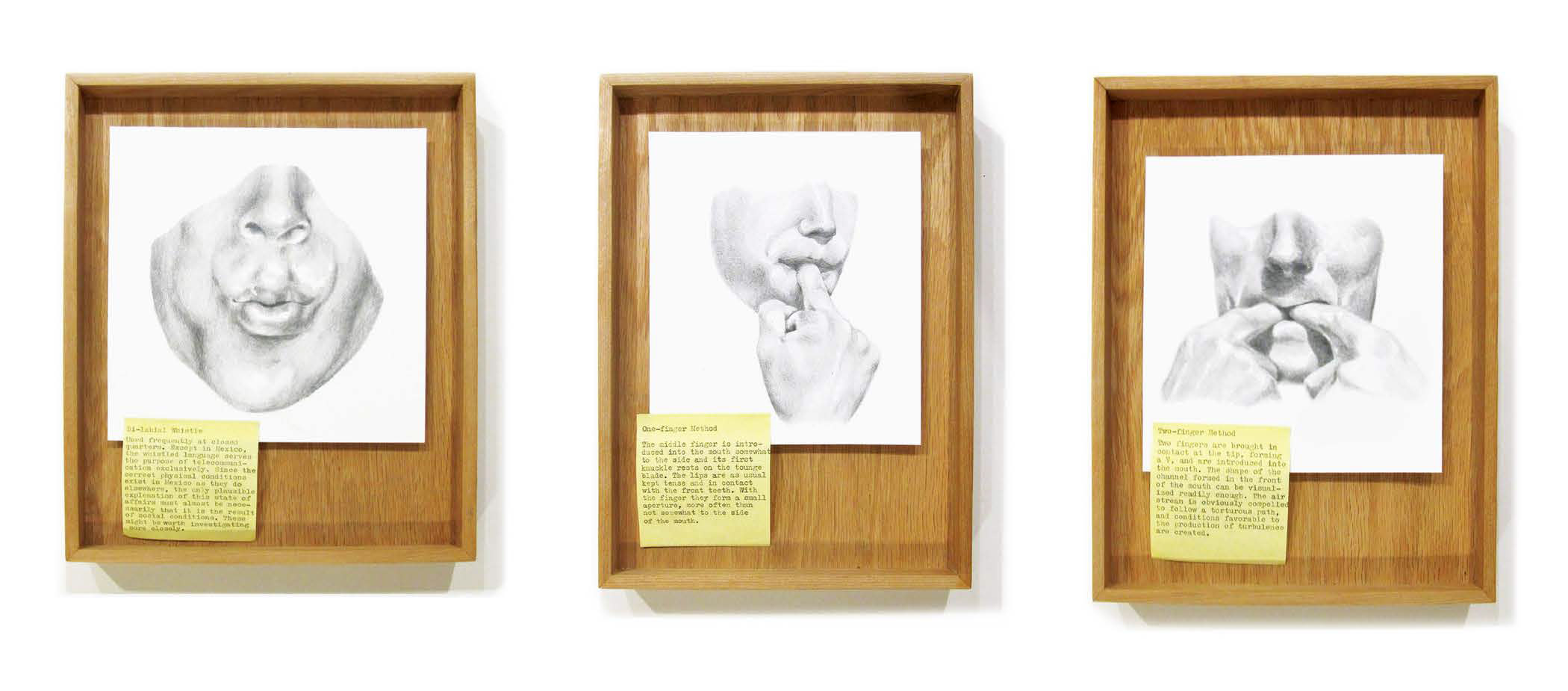

The Language of (Non)communication

Porras-Kim’s work has centered around the theme of language throughout her career. She is particularly interested in undeciphered languages and how we can approach information that is beyond our current understanding. One of her pieces, Whistling and Language Transfiguration (2012), which was featured in the Working for the Future Past (2017) exhibition at the Seoul Museum of Art, is a sound work created on a vinyl record that deals with the tonal Zapotec language used by indigenous people in the Oaxaca region of Mexico.[1] Since the 16th century, the Zapotec people have used their language as a strategic tool for resisting Spanish colonizers by mimicking words through whistling and disguising their conversations as music. Porras-Kim’s attempt to document the endangered Zapotec language with whistling suggests the potential for her work to function as an epistemological tool beyond the context of contemporary art. Additionally, she has focused on the Rongorongo script, an undeciphered script, and has worked on a series of text works since the early 2010s. In her works, she recreates the hieroglyphic symbols found on Rongorongo tablets on Easter Island through drawing, separating and reassembling each character into new forms to derive new meanings.

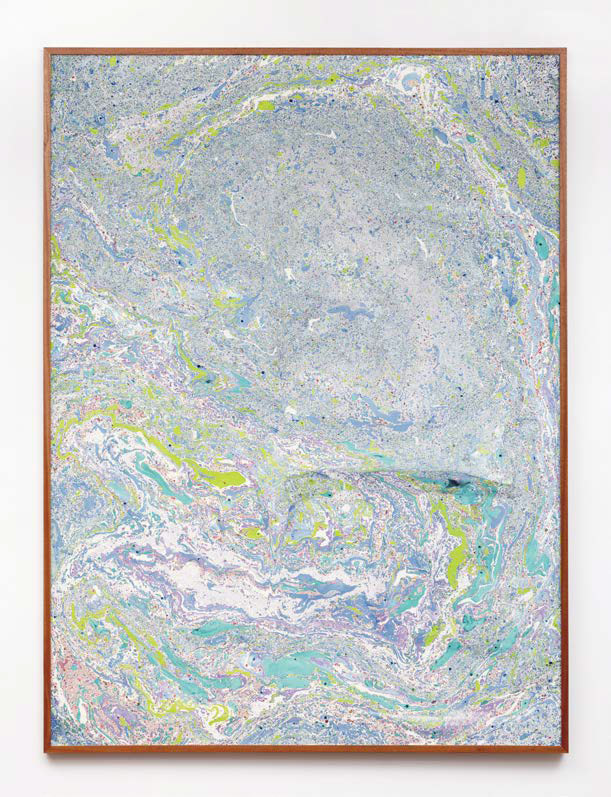

In one interview, Porras-Kim raises the question, “Would the object like the language used to describe it?”[2] By challenging the traditional methods of introducing and documenting museum collections, she often urges institutions to consider practical actions and changes. She presents her findings and solutions in the form of letters to museum directors, outlining issues she has researched and discovered, along with specific ways to address them. These one-page letters highlight her ongoing discussions with leading museums worldwide and add context to the drawing or installation works they accompany. In her process of expanding the scope of her exploration from undecipherable languages to the language systems contemporary institutions use to document artifacts, the artist even attempts to communicate with the dead. A terminal escape from the place that binds us (2022) stems from the awareness that unidentified remains housed in the Gwangju National Museum exist merely as classified codes, stripped of their humanity. Through shamanistic rituals to communicate with the soul of the dead, she inquires where the deceased would prefer their remains to be interred instead of in the museum. Visualized using marbling techniques, a map shows the locations indicated in the ritual; it can also be seen as a result of the artist’s search for an appropriate language and method to communicate with the souls in the afterlife. Given her various approaches, how can we best articulate or summarize Porras-Kim’s artistic practice? Perhaps her works exist as letters that can be combined into countless possible permutations, anticipating that we viewers and distant future generations will derive new meanings from them.

[1] Gala Porras-Kim, “Interview: On the Afterlife and Happiness of Objects,” https://13thgwangjubiennale.org/ko/minds-rising/porras-kim/ [Quote retranslated from Korean]

[2] Refer to the following article for the artist’s research on Zapotec: Gala Porras-Kim, “Whistling and Language Transfiguration: Zapotec Tones as Contemporary Art and Strategy for Resistance,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 96 (2016), pp. 233-237.

‘문화체육관광부와 (재)예술경영지원센터의 지원을 받아 번역되었습니다.

Korean-English Translation of this book(or text etc) is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service’

© (주)월간미술, 무단전재 및 재배포 금지