Kim Yun Shin

Will to Transcend Toward the Absolute

:Kim Yun Shin’s Painting-Sculptures

ARTIST REVIEW

Kim Yun Shin graduated from the Department of Sculpture at Hongik University and later majored in sculpture and lithography at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. She also founded the Korean Sculptress Association. In 2008, the Museo Kim Yun Shin was established in Buenos Aires. After moving to Argentina in 1984 and she returned to Korea in 2024. Some of her notable solo exhibitions include Kim Yun Shin at Kukje Gallery (2024) and Kim Yun Shin: Towards Oneness at the Seoul Museum of Art Nam-Seoul Museum (2023). Prominent group exhibitions include the 60th Venice Biennale (2024), Yesterday and Today of 15 Korean Abstract Artists at the Ahn Sang Cheol Museum (2015), Green Life at the Korean Cultural Center Washington, D.C. (2012), Stone Land at the Iksan International Stone Culture Project (2012), and Encuentro at the Korean Cultural Center in Argentina (2011), among many others. Her works can be found in the collections of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon, the Seoul Museum of Art, the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Modern Art in Mexico, the Beijing International Sculpture Park, and the Rosario Central Post Office, among others.

Will to Transcend Toward the Absolute

:Kim Yun Shin’s Painting-SculpturesKim Yi Soon Art Historian

II.The Journey to Painting-Sculpture

Kim Yun Shin spent a long time integrating painting and sculpture to create her unique painting-sculpture. Her artistic evolution can be categorized into several stages: lithography in the 1960s, ‘stamping’ objects on canvas in the 1970s, oil painting on canvas in the 1980s, coloring wooden sculptures after 2015, and finally, painting with acrylics on sculptures made from recycled wood after 2021.

1.Lithography: The Origins of Painterly Sculpture

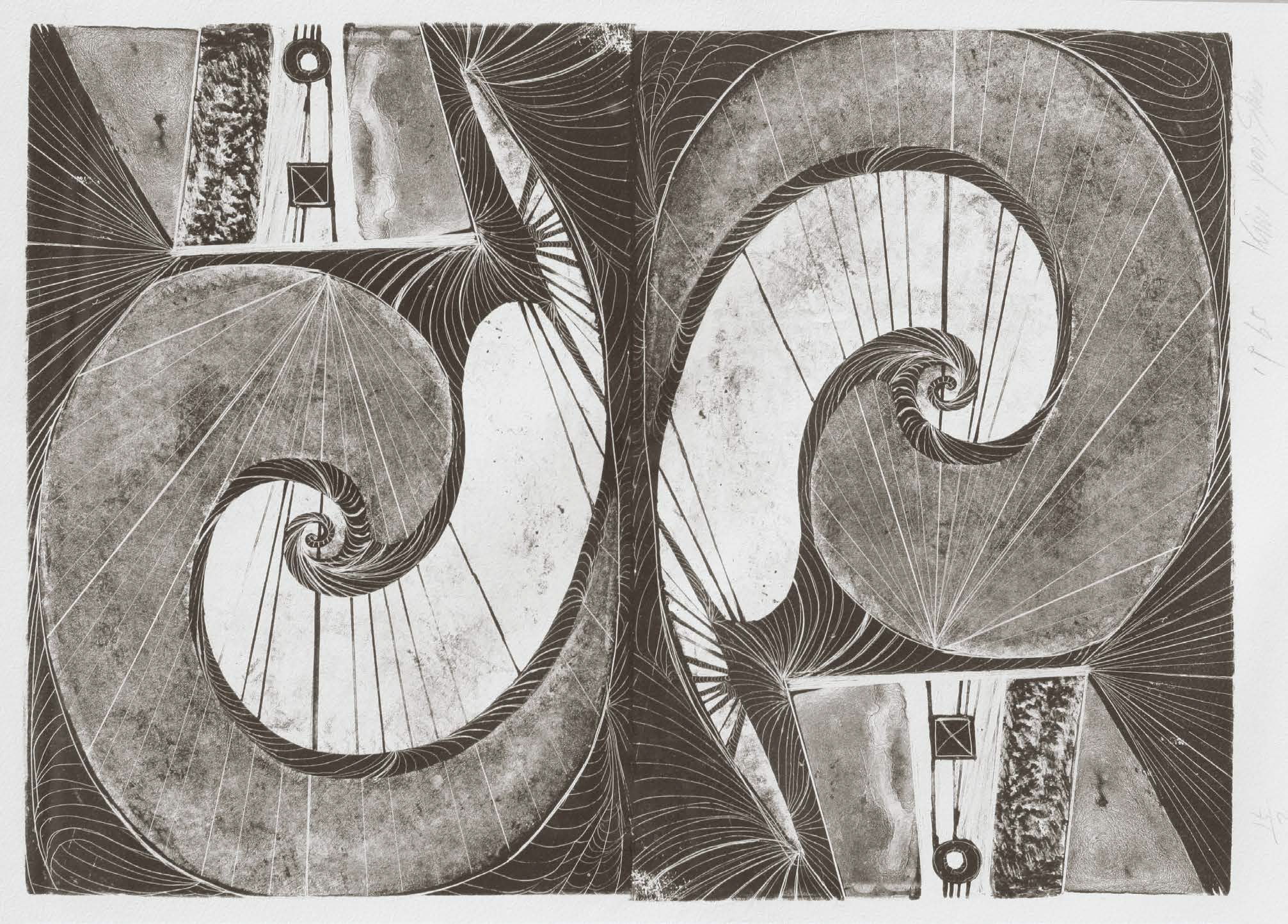

Kim began her artistic journey while studying lithography in France. In 1965, she enrolled in the sculpture department at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but later transitioned back to lithography after her advisor passed away. During her time in Paris, she created numerous line drawings despite primarily working in sculpture. One of her lithograph work “예감” (Premonition) was recognized as the best student work and featured on Parisian TV. This piece incorporated spiral shapes reminiscent of Eastern Taeguk patterns, with delicate lines spreading across the surface. Another work in the Premonition series focused on geometric shapes and lines, resulting in a dynamic interplay of circles, rhombuses, and lines of varying thickness. While it may bear a resemblance to the view of the Eiffel Tower’s iron structure from below, Kim’s lack of interest in representing actual visual objects implies that it should be regarded as a purely abstract, line-centered work.

2.Stamping: Traces of Vibrant Life

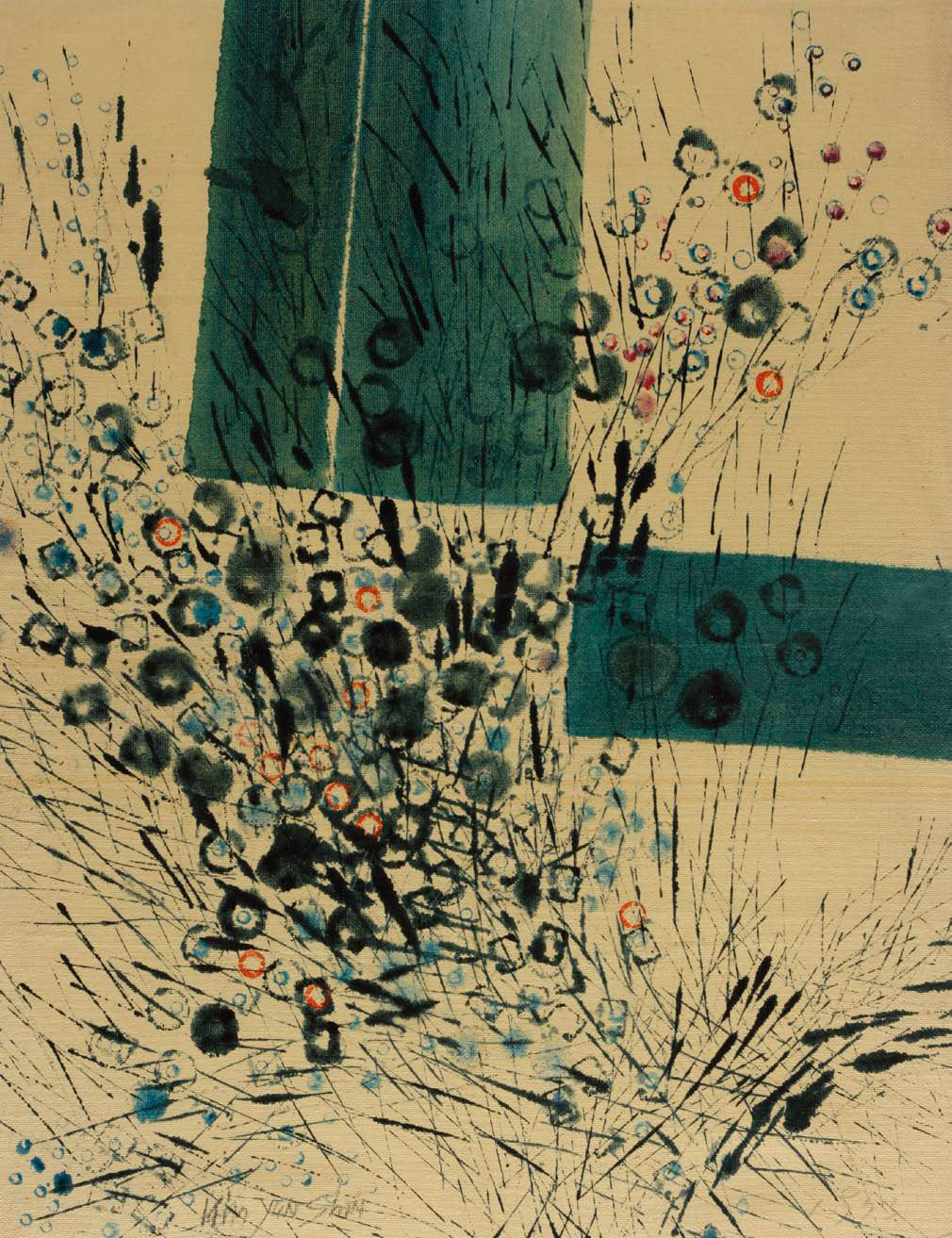

In the early 1970s, Kim created paintings using print ink on everyday objects to leave their marks on canvas, essentially adapting printmaking techniques. In the 1972-73 series Myth of the Constellations, she expressed color fields by stamping sponges soaked in paint, created circular patterns with brush cap imprints, and used construction chalk lines to draw lines, making abstract paintings in her unique way.

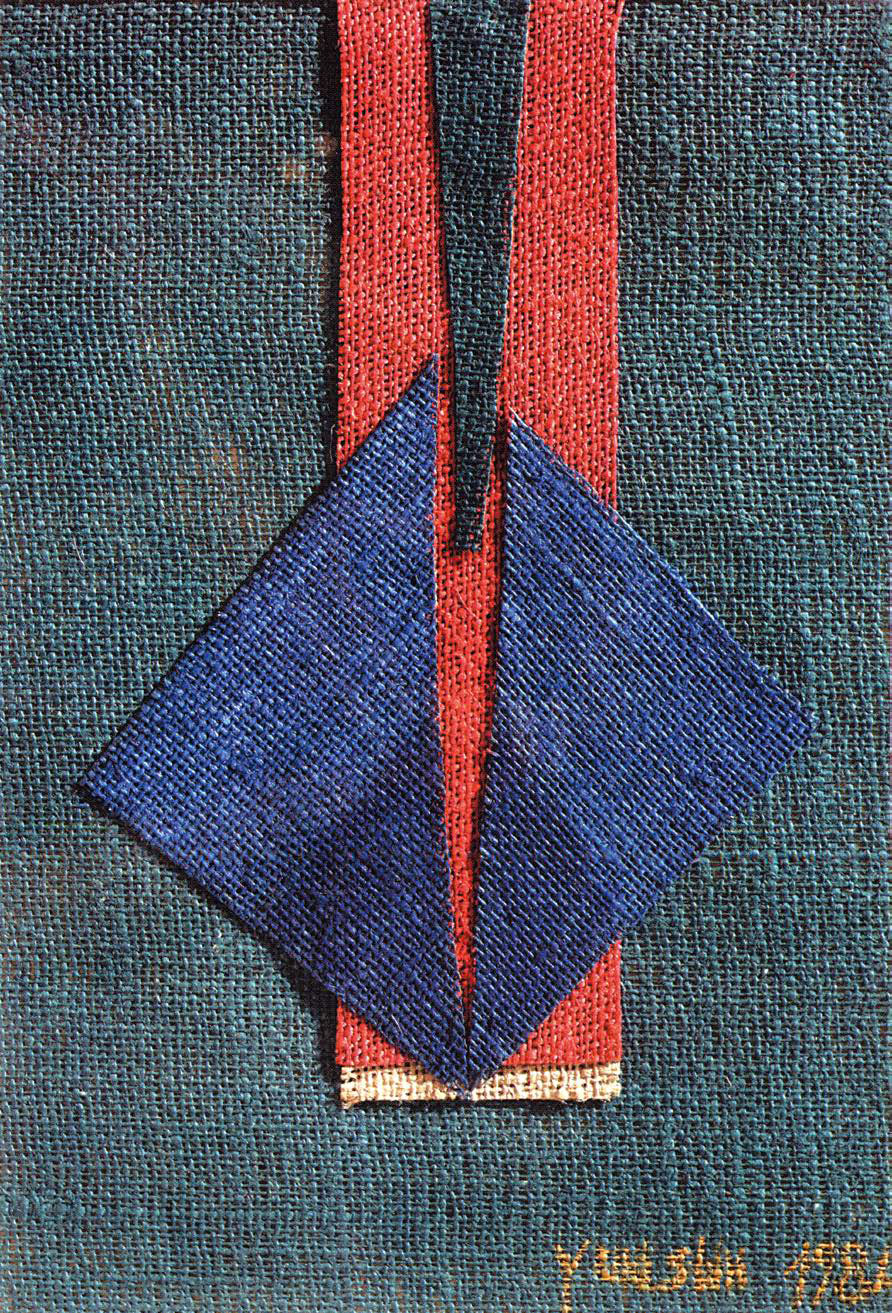

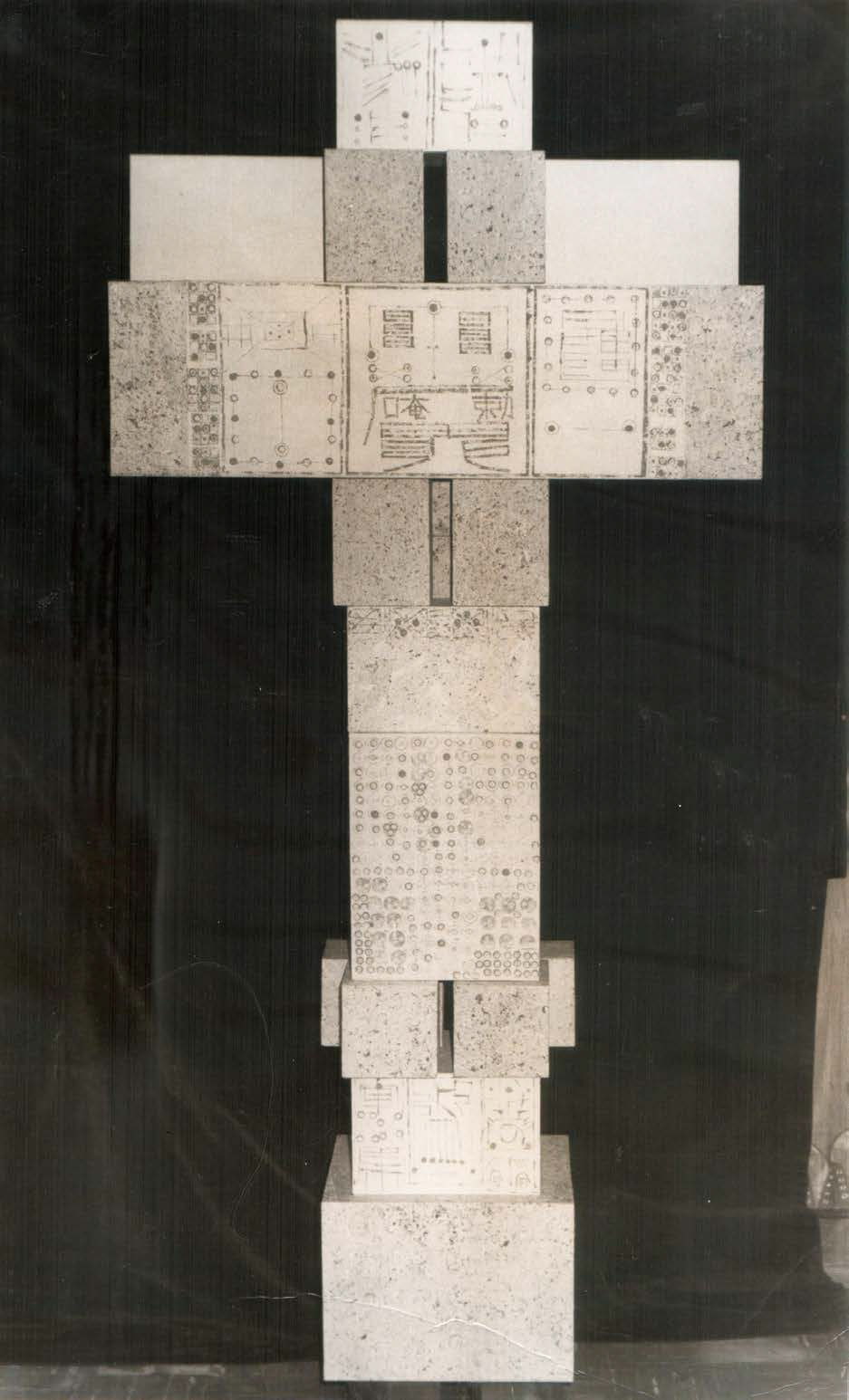

The stamping technique extended to her three-dimensional works. The piece Eternal Guardian of Freedom-Loving People of Peace, exhibited at the 1973 São Paulo Biennale is a crucifix-shaped assemblage of wooden boxes. In addition to the aforementioned techniques, the sculpture’s surface features talisman-like images printed on hanji (Korean paper), lending an oriental atmosphere. It is an outstanding early example of the fusion of painting and sculpture in Kim’s art, which can be seen as the origin of her recent painting-sculptures. This format of adding painterly expression to sculpture is also seen in Aspirational Desire (1973) housed at Hongik University, where geometric forms like arrows are expressed in relief on the surface. In 1975, she created similarly titled geometric abstract paintings Aspirational Desire I and Aspirational Desire II, which heavily feature arrows and triangles. These works reflect her interest in geometric abstraction and the formation of a religious notion that “art is a reflection of the inner soul,”[1] a perspective that persisted throughout her life. Although she did not actively exhibit paintings in the early 1980s, she produced some color-field abstract oil paintings.

[1] “Song of Eternity: 60 Years of Kim Yun Shin’s Artistry,” Monthly Dance and People (춤과 사람들), 2015, p. 40. (Original Korean title: 「영원의 노래 · 김윤신 화업 60년」)

3.Combining Sculpture and Painting

After moving to Argentina, Kim began creating collage works using locally sourced dyed fabrics. Although she had previously worked with fabric prints in her collages, this technique was not new within her painterly oeuvre. Her piece titled Wish features red, green, blue and ochre fabrics cut into geometric shapes and assembled into a color field abstract piece, reminiscent of her 1975 work Aspirational Desire in both form and content.

Initially, Kim’s focus in Argentina was wood sculpture, as wood was the reason for her relocation. She also created sculptures from onyx and semi-precious stones from Mexico and Brazil, showcasing the unique colors and patterns of these stones. It took about 15 years before she resumed painting, but painterly expressions were already evident in her earlier sculptures.

Let’s talk about her wood sculptures. At first, she made wood sculptures by carving raw wood with a chainsaw to create the basic shape, leaving the surface without bark to showcase the material’s natural color and pattern. Later, she started engraving repetitive lines on the surface which is also seen in her lithographs. This engraved line expression actually appeared as early as her 1960 cement work Ancient Myth. These oval-shaped sculptures that looked like traditional Korean jangseung totem poles no longer exist, but their surfaces were lined and painted bronze. The wooden bases were either patterned with gouges or scorched to give a painterly effect. In addition, her welded iron sculpture Will to Regenerate (1962), which she submitted to an exhibition before going to France, depicted a three-legged crow or phoenix. Through repeatedly attaching wire segments to the surface, she maximized linear expression. This shows that Kim’s “painting-sculpture” is not just influenced by one thing or developed in a linear way, but rather is a manifestation of artistic inspiration that took root, grew, and flourished over time. It was around 2000 when Kim started painting directly on wood sculptures again, after being exposed to Mapuche indigenous art.

Kim’s sculptural work displays a painterly expression, particularly evident in her stone carvings. She works with onyx and semi-precious stones from Mexico and Brazil, preserving the natural texture of the raw stones to reveal their intrinsic beauty, resulting in very painterly works. For instance, Add Two Add One, Divide Two Divide One No. 719 (2002) features a half-moon shape spread out like a fan, with no additional artificial manipulation applied. The purple in the raw stone’s smooth cross section creates a harmony with the irregular brown and white patterns covering the surface. Kim’s stone sculptures highlight the stones’ inherent mystic patterns and a wide variety of colors such as orange, blue, red and purple.

Around 1998, Kim began creating oil paintings on canvas. She turned to painting as a break from the heavy labor of using a chainsaw, even taking small canvases on her travels to paint. Her canvas paintings now outnumber her sculptures, totaling over 1,000 pieces.

Kim’s painting manner underwent significant changes over time. In her piece Joy (2002), created during a period of intensive painting, geometric shapes such as triangles and circles, along with diagonal lines and flame patterns, dynamically flow across the canvas, giving it a lively energy. These features can be traced back to her early 1970s work, when she first used object stamps and repetitive diagonal lines in her wood sculpture. Another work, Song of My Soul (2006), uses the traditional Korean Obangsaek colors—red, yellow, blue, green, black, and white—to create abstract forms in semi-circular and rectangular color fields. Notably, she created lines using a knife to scrape the surface layer of paint; the countless delicate lines expressed by scratching the paint animate the canvas with a vibrant, almost pulsating energy.

4.“Painting-Sculpture” Born in an Isolated World

During the pandemic, Kim explored new forms of expression. Faced with the challenge of severed connections, widespread isolation, and a disrupted supply of sculptural wood, the artist turned to creating sculptures using scrap wood. After cutting and assembling various types of scrap wood, she added colors to complete her works. By utilizing wood pieces of different shapes and sizes, Kim’s resulting sculptures featured different forms from each of their four sides. Similar to Picasso’s use of Cubism to present different perspectives with varying shapes and colors in Glass of Absinthe (1914), which looks like an entirely different picture depending on the viewpoint, Kim created dynamic “painting-sculptures” by painting each of four sides with different images.

She created paintings by filling canvases with dots and lines, using various objects dipped in paint instead of brushes. The stamping technique she used has its roots in her 1960s lithography. Through the process of stamping countless dots and lines onto large canvases, she found it to be a meditative practice, akin to prayer.

Kim freely traversed the boundaries between painting and sculpture by cutting and assembling wood while applying and scraping paint on the canvas. As she put it, “I had to paint to sculpt, and I had to sculpt to paint.” In her work she saw the unification of the two genres, resulting in a new paradigm of “painting-sculpture.”

III. “Add Two Add One”: Unifying Life and Art

In her works since around 1977, Kim has consistently used the concept of “Add Two Add One Divide Two Divide One” (합이합일 분이분일/合二合一 分二分一) in her titles. This concept comes from her process of cutting and joining logs to create her pieces, and is linked to the idea that everything in the universe is a balance of yin and yang. This concept also applied to her painting, where dots, lines, and colors flow freely on the canvas. These elements represent the artist’s primal energy or life force within the artist, which she sometimes refers to as her “spirit.”

The concept of “Add Two Add One Divide Two Divide One” extends beyond Kim’s art. Life and art are two realms, but for her, life (or religion) and art have never been separate. This makes “Add Two Add One” a concept that encapsulates her entire existence. Kim’s artistic drive cannot be easily explained by her desire for self-accomplishment or competitive aspiration. Her creative impulse stems from a “desire to be blessed by the Absolute.”[1] If her artistic drive had been based on worldly fame or recognition, she would not have been able to dedicate herself to a life of uninterrupted creation in Argentina, halfway across the globe from Korea, for 40 years.

When we face her works that have traversed that long period, her confession resonates more profoundly: “As if conversing with the Absolute daily and every moment in prayer, my sculptural language transcends time and finitude, continuing as the series Add Two Add One Divide Two Divide One, a totality of combining and dividing not only within the work itself but also with the surrounding natural world as the whole.”[2] This might be why we are so fascinated by her art and by her will to transcend, making life art and art life, being two and one simultaneously.

[1] Kim Yun Shin, “Attempting to Converse with Materials,” Artist’s Note, March 2022. (Original Korean title: 「재료와 대화를 시도하다」, 김윤신 작가노트, 2022.3.)

[2] “First-Generation Sculptor Kim Yun Shin: ‘Sculpture is a Journey to Find My Heart,’” Art Chosun, June 15, 2015. (Original Korean title: 「1세대 조각가 김윤신 “조각은 내 마음을 찾아가는 여정”」)

‘문화체육관광부와 (재)예술경영지원센터의 지원을 받아 번역되었습니다.

Korean-English Translation of this book(or text etc) is supported by Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and Korea Arts Management Service’

© (주)월간미술, 무단전재 및 재배포 금지